To Capture Perception: On the Experience of Immersive Studies

Teach your writing students to feel the visceral aspects of life, to trace their subjects with powerful word images, and you have helped them to succeed. Herein we find the essence of communication, the ability to capture perception and create immersive reading experiences across the disciplines. (My Thought for the Day)

Our Story Begins

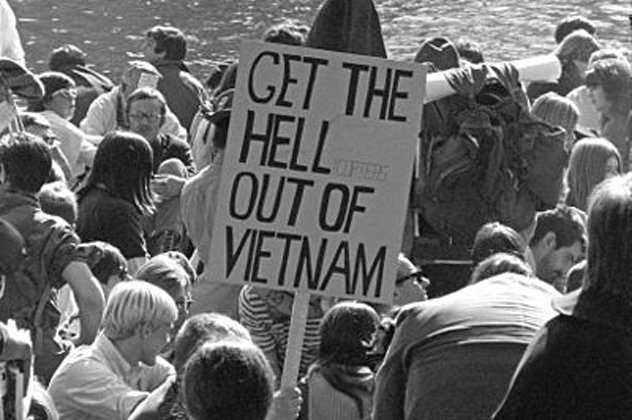

Many years ago, I had a history teacher who pushed the bounds of 1980s education, challenging us--a group of cynical teenagers--to experience the horrors of the Vietnam War in immersive fashion, one paperback book and guest lecturer at a time.

If I recall correctly, it was 1988, and the teacher in question has since faded into memory, apart from the moment she presented us with our books. There, on the surface of her wooden desk, she dropped a torn paper bag, overflowing with war journals from ordinary soldiers. I remember the fragrance vividly, the glorious pulp used to publish trade paperbacks of the era. And I remember the covers, as well, the pictures of battle that were, for us, the history of our fathers and uncles. Actually, my father had fought in the Second World War, but my peers had grown up with the succeeding generation--distinct in many ways. At any rate, the class was a bit of a luxury, an opportunity to spend two weeks focused on a single subject, reading, discussing, and hearing from guest speakers until the material became, perhaps, a bit unbearable. And that was the denouement, the dramatic complication that opened our eyes.

Revealing an Era

Everything about the 1960s was designed for immersion and sensory assault, social engineering that started with a drizzle and, over time, ended with a flooding downpour. We spent each class session watching video cassettes of old news footage, or, more accurately, propagandized media presentations of war. It was all quite fascinating. During the late 1960s and early 70s, scenes of jungle combat issued from televisions nationwide, and body counts were read by news anchors, as if journalists were keeping score for the public. Eventually, after such immersion and so much study, we saw flaming jungles when we closed our eyes at night. From there, the dramatic tension continued to unfold.

After the first week, the narratives of history attended us in the classroom, and throughout the evenings, as well, making it clear that the war in Vietnam was essential for us to study and understand. Remember, this "conflict" became something of a national disgrace, as servicemen were spat upon, and the government refused to honor the memory of fallen soldiers. During the 1970s, our teachers generally avoided the subject, providing, at best, a brief summary of events--and only when pressed by our persistent questions. Gradually things changed, and we became the first generation to learn anything substantial about the war, the first ones to have our questions answered in a sincere way. And this is why I remember our teacher with fondness.

Immersive Study (Circa 1980)

In those days, it was all about human interaction, rather than electronic mediation, the opportunity to meet in-person and share on a meaningful level. For our class, the details of history emerged from books and conversations, the stories of guest speakers filling long afternoons with suspense. More than anything, however, we experienced tangible communication, a connection that established a safe space for all concerned. In the end, our class on the Vietnam War became a vehicle for conveying experience; we felt a connection with those who served--veterans who were routinely denied benefits and appropriate honors--and learned history directly from their lips.

Indeed, I felt like I had captured a measure of perception and, moreover, experienced history on a human level. Granted, such atrocities as the My Lai Massacre of 1968, in addition to many other incidents, were not part of our curriculum. And complex foreign policies, the political contradictions at work during the 1960s, were also beyond the scope of our class. Those studies would come later for me, after additional years of reading and contemplation. However, thanks to the innovative instruction I received in high school, my undergraduate (and graduate) history courses were fruitful in no small way.

As for the veterans who visited our class, men who shared the deepest and most scarred parts of themselves with us, I thank them. The power of immersive study is felt not only by students, but also by guest speakers who share the beauty and sorrow of their stories. As I look back, I realize the true meaning and potential of social science education.

Today's concept of immersion--via technology--has more to do with sensory assault than education, manipulating perception to create illusions rather than clarifying reality. This is a tragedy, so I hearken back to previous decades. As I learned in high school, there is simply no substitute for reading, discussing, and hearing guest speakers in person, allowing the tension of awkward silences and tears to prevail. Education is, on many levels, communal and flourishes through immersive studies of the old variety.

Update

Eventually, I was able to remember the name of that teacher, the young woman who understood the meaning of community and education, on a deep level. She went on to become a university administrator, holding high-level positions at various institutions. As for the students, most of us opted not to join the military.

For Further Reading

The Library of Congress has many useful resources for those researching military life, and the compelling experiences of veterans. "'My Trusty Pad': Diaries in the Veterans History Project" is an article you will enjoy, published by Megan Harris in 2014.

Brant, Toby L. Journal of a Combat Tanker, Vietnam, 1969 (Vantage Press, Incorporated) 1988.

Linz, Ed. A Filthy Way to Die: Collected Memories of the Vietnam War (Exchange Publishing) 2023.