The Eames Chair and Optimism: The American Aesthetic at Midcentury

From my childhood in the 70s, I recall the orange chairs of waiting rooms, plastic décor elements which seemed very much like toys lost in the world of adults. These were Eames chairs, quietly enjoying the end of their prominence in interior design. More than functional, as they combined the embrace of a lounge chair with the austerity of fibrous plastic, these pieces created a sense of playfulness in the postwar era. In short, this innovation from Charles and Ray Eames speaks to the heart of optimism, with the strength of practicality as well as the lightness of humor, very much in keeping with the mood of life at midcentury.

If progress had an aesthetic, it was visible shortly after the Second World War, as amenities became part of a new domestic lifestyle. Imagine living in Southern California, opening the curtains of your ultra-modern home in the canyon, surrounded by pungent eucalyptus trees and morning sun. The mood in your little enclave is one of fulfillment. After wartime rationing, and the horrors of combat, you are raising a family in the suburbs, enjoying the dream for which you have sacrificed and labored. And what better way to mark this era than with cheerful architecture and sleek industrial design? You can enter your kitchen, squeeze oranges in a modern juicer, gaze at abstract paintings, and drive to work in the comfort of your luxury car — made in America. Indeed, the years following World War Two were heady times for some Americans, not least architects and artists. And this is the milieu into which the Eames creation emerged, a flourish of color erupting into the modern design landscape. I remember it well.

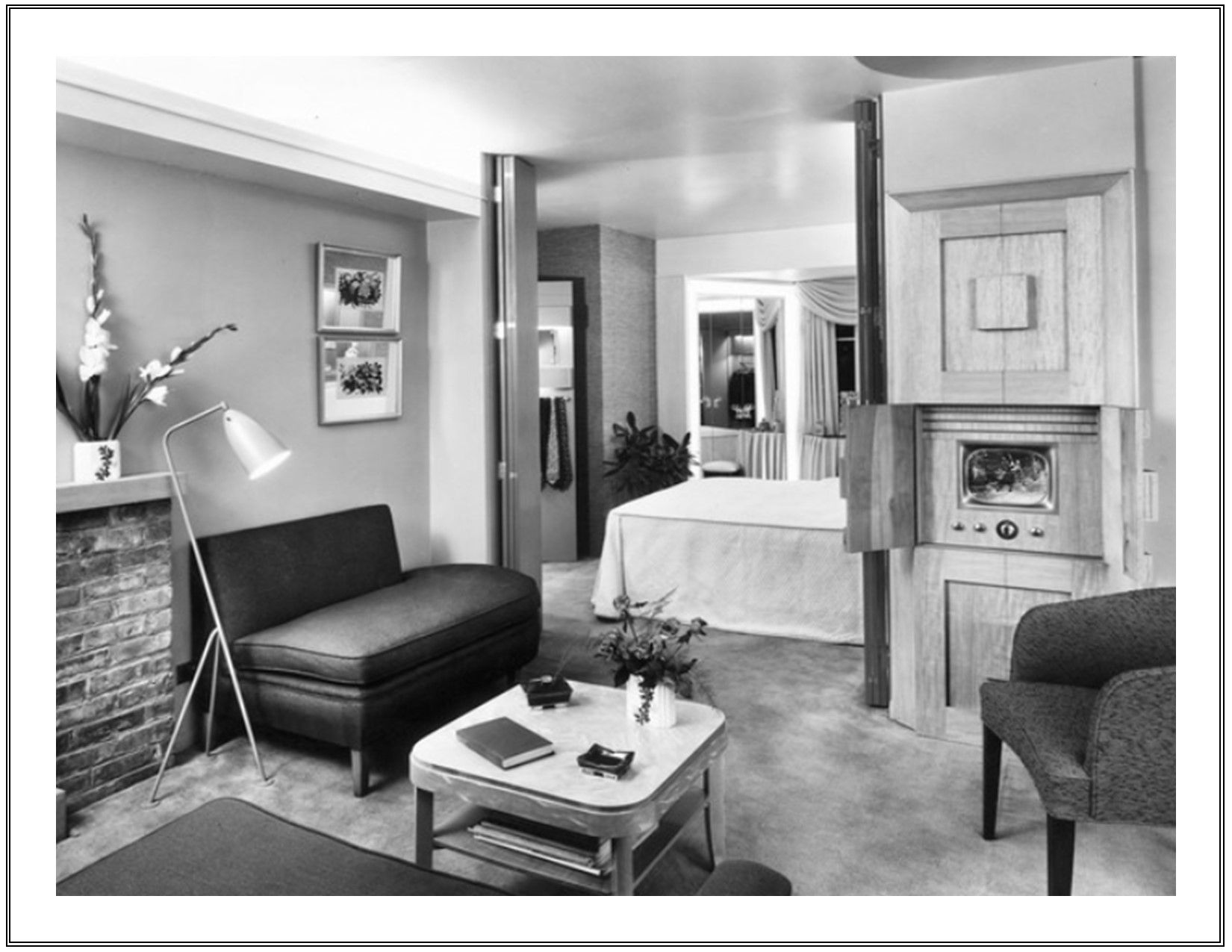

I explored a number of interesting living rooms, decades ago, as I trekked through Los Angeles with my mother, visiting friends and relatives. The spaces were all quite memorable, the sunken rooms, open-plan interiors, and those flat, unadorned sofas delineating “conversation areas,” as we called them. Everything had its place in compositions that were, at once, richly adorned and spare, prosperous but delicately restrained. Even new innovations, like entertainment centers, were artfully conceived. In those days, televisions were made to resemble furniture more than instruments of technology; discrete boxes, sometimes covered with sliding panels of wicker — perched on wooden legs similar to those supporting the sofa — would complement rather than overshadow the décor.

Televisions at midcentury were still a novelty, awkwardly placed amid more traditional furnishings. The scope of homelife in a prosperous nation was quickly being defined, from luxury and entertainment to functional elements. Thanks to progress, everything old could become new and sleek, taking on a refreshed aura. And this brings us to the subject of ambience and furnishings, thoughts on how we relate to our interiors.

The furnishings of living space are analogous to the punctuation of written language. Both elements are functional as well as inspiring when used with care. And, by the middle of the twentieth century, interiors were beginning to develop along these lines, a happy marriage of utility and form, exemplified wonderfully by the Eames chair. Bright color and the use of plastic changed the modernist vernacular, the visual aesthetic largely established by Mies van der Rohe — in particular, with his Brno chair. The newer Eames design, although a bit less luxurious, made use of upgraded production methods and appealed to an expanding middle class. And it did so with a high degree of flair. By establishing playfulness, even in the most serious spaces, the Eames chair occupied an interesting place in the design world; it offered an orange interruption to the beige expanse of business days, whimsically solving the problem of where to sit in a waiting area. And how did such vision originate? Here, we consider the thoughts of the designer. In a statement issued by the Eames Office in relation to the MoMA Low-Cost Furniture Competition, we learn:

The form of these chairs is not new nor is the philosophy of seating in them new — but they have been designed to be produced by existing mass-production methods at prices that make mass production feasible and in a manner that makes a consistent high quality possible. (1)

These pieces conformed to the needs of consumers as well as mass-producing manufacturers, quite effectively, without sacrificing midcentury élan. Without a doubt, the Eames chair is very much the emblem of a flamboyant — yet eminently practical — design era. And how have things changed?

The piece I remember from childhood looks quite a bit like the Eames Molded Plastic Wire-Based Side Chair, now available online for between $315 and $600, an amount which would surely have astounded its designers. An iconic example of furniture, it appeals to those who appreciate design heritage. The simplicity is so unassuming as to call out for attention and a certain degree of admiration. Aside from being comfortable, the Eames chair eased the dreariness of countless waiting rooms, elevating these spaces into something cheery, or at least tolerable for those awaiting root canals and checkups. In so doing, it somehow reflected the spirit of the times, the sense that things were good and would likely remain that way. Perhaps optimism is nothing if not short-sighted. For a different view of the midcentury aesthetic, we can remove the chair from its place in waiting rooms and situate it in the home environment, specifically in the Case Study Houses of postwar America.

A New Vision of Daily Life

After serving occupation duty in the smoldering cities of Europe, American soldiers began returning home to resume their lives. Of course, this migration required new housing projects, not just a series of plain dwellings — or boring bungalows — but something innovative, places where young families could thrive and feel at home: enter the historic endeavor sponsored by Arts and Architecture Magazine.

Thirty-six designs were created for Southern California in a 1945 project, “experimental modern prototypes” that fueled the postwar housing boom. (2) Here, it’s important to note that many designs were not constructed and remained theoretical, in keeping with the research emphasis of the program. Neither did the work change the way in which housing served the rising middle class. Rather, the project did produce a memorable collection of dwellings, noteworthy structures from the previous — more optimistic and economically stable — age of architecture. (3)

Now that hillside residences are reserved for the wealthy, Case Study Houses (much like orange Eames chairs) are the stuff of nostalgia, symbolizing an era of triumph and prosperity unlikely to be repeated. Perhaps, more than anything, midcentury accoutrements are symbols of validation; they tell us that hard work, dutiful service and sacrifice are indeed rewarded, and that ordinary men and women can enjoy the fruits of their labor, passing on beautiful family homes to their heirs. Attending that vision, we find massive windows, bright hallways and outdoor lounge areas that easily lift one’s spirits. Walk through a home from the Case Study Program, maintained for historical accuracy, and you will see what I mean. Everything about it declares the aesthetic of optimism, shouting it boldly for all to hear, “We won the war, and our lives reflect the rewards of our service.”

In such an environment, it’s hard to think that anything but prosperity could be inherited by subsequent generations. Although little more than a fading and naïve dream today, the era is still pleasant to recall. For my part, the scent of eucalyptus always invokes memories of midcentury architecture, and my childhood journeys through its décor. Although I was born in 1970, many of my parents’ friends preferred older furniture to the shag carpets and beanbag chairs that were becoming popular. And their service during World War Two made them part of that heroic, fortunate group of Americans, people for whom hillside houses and cheerful orange chairs were made. With this in mind, we can consider the meaning of home, its symbolism, as well as its many functional aspects.

The Poetics of Space, a deeply philosophical treatment of architecture by Gaston Bachelard, comes to mind. “My house,” writes Georges Spyridaki, “is diaphanous, but it is not of glass. It is more of the nature of vapor.” (4) Bachelard goes on to tell us that “Spyridaki’s house breathes.” In relation to the Case Study House Program of 1945 through 1966, this notion is fascinating. I imagine the diaphanous feelings of exuberance that characterized the era, the houses with their elongated profiles and intimate relationship with canyons and hillsides. At their finest, these designs merged into desert landscapes unobtrusively and with elegance. The American midcentury aesthetic was truly something of a vapor, a dream of the future which, quite sadly, did not materialize as anticipated. As for the way in which a house breathes, expanding and contracting according to the lives it shelters, we can easily envision this process unfolding in a Case Study structure.

Tangible Expressions of Myth

Each home was designed to expand and contract for a growing family, not in dank urban tenements, but out west in the sunlight of suburbia, where prosperity could flourish for the new middle class. Both glass and vapor, these structures were not only experiments in architecture but commentaries on family life, spaces reserved for privacy as well as communion. Again, the myth that labor and patriotism lead to automatic rewards was prevalent, a part of the American mindset at midcentury, expressed in a collection of houses that few people can afford today.

So, as we consider the Eames chair, and its location in the midcentury aesthetic, we must also give place to the dreams it inspired, the vapor that produced new ideas about homelife and what we, as Americans, might anticipate for our future. Of course, an Eames chair is now a luxury rather than a mass-produced bit of furniture for people on a budget. And this in itself is quite telling. If a lifestyle that once constituted modest luxury is now mythic and out of reach for many Americans, what does this tell us regarding midcentury dreams? Well, they were just that, dreams that once had their place in the national psyche. Although midcentury life has faded, there are scattered elements that remain, bits of furniture that remind us of a beautiful postwar narrative.

We conclude with an image of an ordinary postwar family who, in all likelihood, would not be able to afford a Case Study House in the current market — food for thought . . .

Notes:

(1) Charles and Ray Eames, Daniel Ostroff Editor. An Eames Anthology: Articles, Film Scripts, Interviews, Letters, Notes, Speeches. Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2015. (p. 73).

(2) Elizabeth A. T. Smith and Julius Shulman, Peter Goessel Editor. Case Study Houses: The Complete CSH Program, 1945–1966. Taschen, Cologne, 2019. (p. 9).

(3) ibid.

(4) Gaston Bachelard. The Poetics of Space: The Classic Look at How We Experience Intimate Places. Beacon Press, Boston, 1964. (p. 51).