Jazz Pianist Hampton Hawes: Remembering a Relative

Originally Published in All About Jazz, 2020

He was my maternal grandmother’s nephew, the thin, handsome relation who grew to befriend my uncle Bob — also thin and handsome — and become a fixture of the postwar jazz scene in Los Angeles. Having worked amid luminaries of the era, Lester Young, Charlie Parker, and Dexter Gordon among them, Hampton was always a fascinating topic of discussion for us. On so many occasions, I sat with my uncle, mother, and grandmother at the dining room table, remembering the rich history of Central Avenue, part of which was the jazz culture of midcentury, and the career of our cousin.

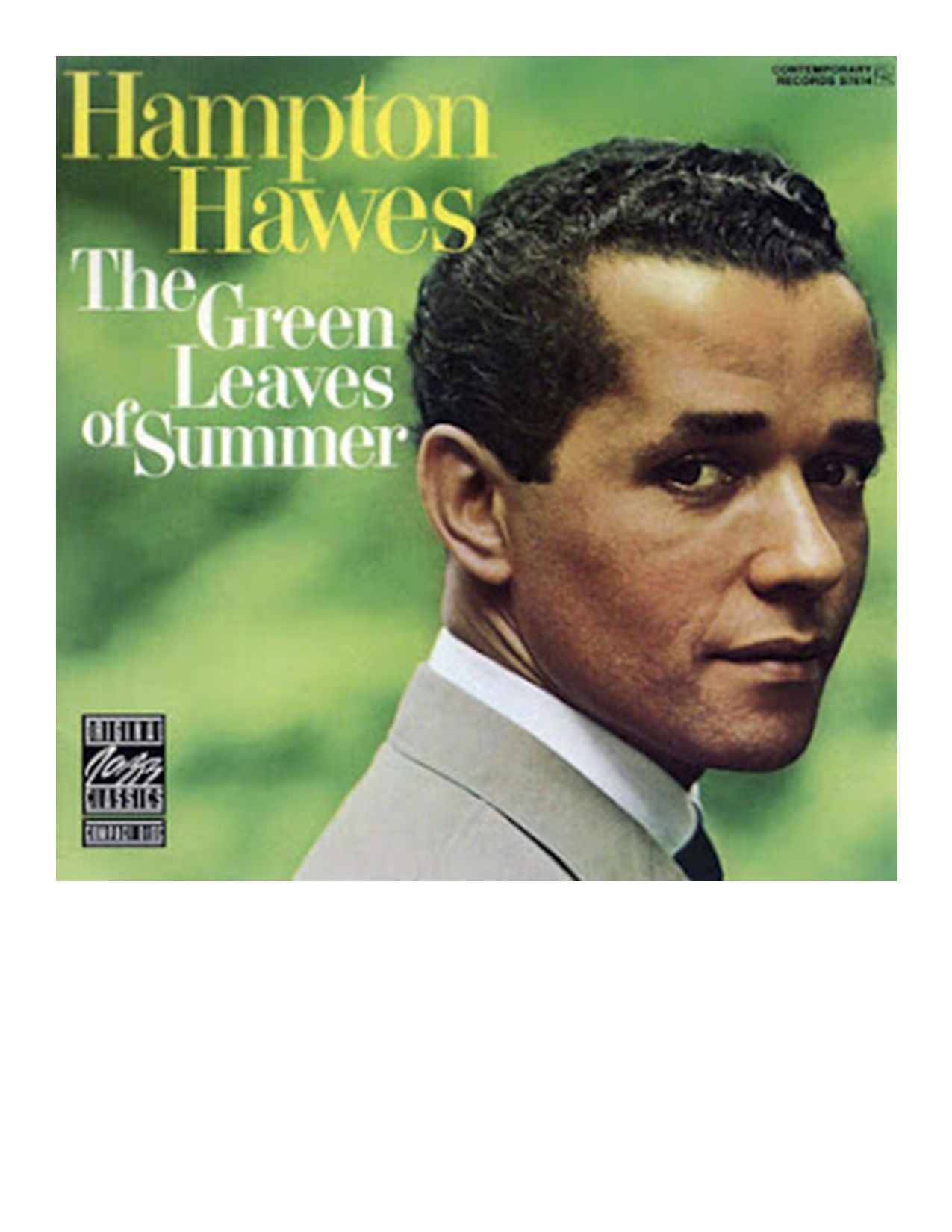

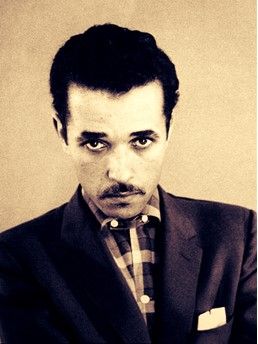

As reported by Hollie West of The Washington Post, on May 25, 1977, Hampton died of a brain hemorrhage at the age of 48, having been admitted to Wadsworth Veterans Administration Hospital earlier in the month. West called him an “exponent of modern jazz piano,” with a “brittle and percussive” style reminiscent of Bud Powell, though less complex. For my grandmother and uncle, such attention to the passing of a family member was surreal, anonymity rather than fame being the norm for us. In the years that followed, Hampton assumed a lofty status in our minds, one we typically reserve for those who succeed brilliantly, struggle, and depart from the world too soon. For me, being too young to have experienced the halcyon days of his career, Hampton became a static image, to some extent, a figure intertwined with memories of my uncle and grandmother. Now, as I approach the age of 50, the complexities of his life are interesting to consider, the choices of his youth being as problematic as they were fruitful.

To those who have studied his life and work, the most glaring aspect of Hampton’s story pertains to his drug addiction and truly lamentable decline, the fact that he faltered so desperately in spite of immense talent and achievement. Of course, the tragedy of addiction is nothing unusual in the annals of music history. But something about the photograph of a frail (rather than simply thin) and haggard (rather than handsome) pianist standing backstage — and looking pained to the point of collapse — still touches me, even now. Indeed, the extant images of Hampton are quite telling. Moreover, I cannot help but marvel at how closely he resembled my uncle Bob, as if the two might have been brothers. In fact, Bob was known by friends and family for playing the piano, by ear, remarkably well.

Last year, I reached out to Ted Gioia, a pianist and scholar who has written about Hampton and the Central Avenue jazz scene. I shared that my uncle and grandmother were quietly a part of the musician’s life, the existence he enjoyed away from the demands of recording studios, clubs, and concert stages. Gioia was warm and helpful, and put me in touch with another researcher, Mark Eisenman, who generously provided me with additional insights into Hampton’s life, issues his relatives often chose to overlook.

Not surprisingly, my uncle and grandmother never spoke about our family’s rather awkward relationship to history, an episode I found chronicled on the jazz website of Leo T. Sullivan. In 1958, Hampton faced a ten-year federal prison sentence for drug charges but declined to expose his associates to prosecution by way of a plea bargain. And, as history would have it, his request for a presidential pardon was favorably received by John Kennedy in 1963, one of the final acts of the administration. Mr. Eisenman emailed me a copy of the document, and thus helped to augment my understanding of a distant relative and the era in which he lived.

What my grandmother did mention was the fact that Hampton’s father had been a Presbyterian minister, and his mother a church pianist, the woman who likely helped him to achieve his unique phrasing and sense of poignance. Hampton’s story was indeed rich with unlikely connections and brilliant nuances, a talented clergyman’s son, engulfed by a lifestyle his parents had condemned. In fact, my mother and grandmother recalled how the elder Hawes would often cry during his sermons, hinting at the great pain a wayward child can cause. And, at the height of his troubles, my grandmother often sat and cried with Hampton’s wife, praying for hope in a hopeless situation. Over the years, the two women enjoyed a warm friendship. For my uncle’s part, he and Hampton’s wife would often visit morning jam sessions at Central Avenue clubs, attempting to locate the musician and escort him home. Although rarely successful in that endeavor, my uncle did have a wonderful opportunity to explore the jazz scene and hear all the greats as they improvised.

After years of wonderful music, as well as the tragedy of heroin addiction, one could certainly argue that our nephew and cousin missed little and did much to assure his own demise. Of course, we, as his relatives, did our best to overlook the tragedy and focus on how deeply he touched those around him. Even now, hearing his work with Red Mitchell and Chuck Thompson, those beautiful sessions from the 1950s, reminds me of how extreme the peaks and valleys of his life were, a story of artistic success interrupted by human frailty. As I wrote to Ted Gioia, I hope that people remember Hampton, above all else, for having been deeply loved and mourned after his passing.