Entering Idaho: A View on American Studies

I spent a few days exploring Provo, Utah and proceeded to Idaho through the beauty of early June, graced by sunlight and delighted by the well-maintained highways that lead north. Yes, I was excited. Although I enjoy the desert sunsets of winter--skies illuminated by distant fire, shades of pink that challenge even the greatest painters--lush farmland provides a change of pace, for which I am grateful. During the drive, I had time to consider the landscape of Idaho along with certain authors I've been reading, two of whom tell a frightening tale.

American Literacy: The Work of Rudolph Flesch and John Taylor Gatto

Education and literacy have long been at issue in our society, sometimes being overlooked in our age of high technology, computer interfaces replacing printed books, social media interaction supplanting human contact. We tend to view communication shortcomings in light of recent years. However, the problem has been with us for quite a while and requires ongoing research.

Why Johnny Can't Read (And What You Can Do About It) was published in 1955. Within its pages, author Rudolph Flesch articulated concern about the state of public education and the illiteracy it fostered--even then, during the glorious postwar era. According to conventional wisdom, the boredom and lack of imagination that characterize compulsory schooling are the main culprits. And why is education like this?

Weapons of Mass Instruction by John Taylor Gatto explores this subject, shedding light on a questionable agenda from previous centuries. It seems that a cadre of wealthy meddlers and their flunkies--William Torrey Harris, Andrew Carnegie, Max Otto, and Horace Mann among them--long ago decided to prime children to play their part in society, growing up to obey those in power, believing what they are told and, most tellingly, losing the skills of high literacy slowly, one generation after another. This is what we call factual conspiracy rather than theoretical conjecture. For proof, we need only reference the historical record and the pronouncements of those who devised American public education.

In every age, men of wealth and power have approached education for ordinary people with suspicion because it is certain to stimulate discontent, certain to awaken desires impossible to gratify. In April 1872, the US Bureau of Education's Circular of Information left nothing to the imagination when it discussed something it called 'the problem of educational schooling*' According to the Bureau, by inculcating accurate knowledge workers would 'perceive and calculate their grievances', making them 'redoubtable foes' in labor struggles! Best not have that (1)

And there is yet more to consider:

Thirteen years later in 1885, the Senate Committee on Education and Labor issued a report which contains this forceful observation on page 1382: 'We believe that education is one of the principal causes of discontent of late years manifesting itself among the laboring classes'. Teaching the means to become broadly knowledgeable, deeply analytical, and effectively expressive has disturbed policy thinkers since Solomon, because these skills introduce danger into the eternal need of leaders to manage crowds in the interests of the best people. (2)

So, the educational mission of the United States was established with these ideas in mind. The management of future laborers--the "human resources" of industry--would make life easier for the best people by keeping the multitudes subdued; indoctrinate the people to obey in silence and labor for the enrichment of their leaders. As we examine the current state of society, and scrutinize corporate wealth, we find ample evidence that this agenda has long been operational and successful.

Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations called for 'educational schooling' to correct the human damage caused by mindless working environments, but Andrew Carnegie, writing 126 years after Smith, in The Empire of Business disagreed. Educational schooling, said Carnegie, gave working people bad attitudes, it taught what was useless, it imbued the future workforce with 'false ideas' that gave it 'a distaste for practical life'. (3)

Yes, a glance at the historical record provides clarity, revealing the true reasons for compulsory education. Again, the evidence speaks for itself. From the documents of policymakers, we discover that the system was structured in a particular way--certainly not for the benefit of the greater part, but for containment (and control) of the many by the few.

I highly recommend reading Gatto and Flesch. Why Johnny Still Can't Read continues the latter's research and expands his scope of inquiry. Even in the heady days of postwar life, the years we recall with fondness, the darker aspects of education were in evidence. With this in mind, Samuel Blumenfeld is also an important author to study.

A brilliant educational theorist, he notes that American children have been moved from language studies to the practice of reading icons and interfaces, pointing and clicking rather than mastering English and thinking logically. Indeed, if children were to acquire high literacy, how would the power structure retain control over society? The evidence argues that the architects of compulsory schooling devised, with great malice, the foundation of Common Core Curriculum--and the mindless confusion it engenders.

Yes, weapons of mass instruction have primed multiple generations for things yet to come. Oh, and if you are my age, you probably recall the "new math" we were forced to learn. Well, you can feel good knowing that you were right. It makes no sense at all, and it was designed that way. Now, we consider the issue of school psychologists.

American Public Schools Inflict Behavior Modification?

It appears so.

Although a study of behaviorism is beyond the scope of this reflection, it's worth noting the influence this -ism has held over education. In short, it is the belief that managing behavior--rather than igniting imaginations and encouraging children to attain high literacy--should be the goal of compulsory education. And this belief is practiced with apostolic devotion, being very much the religion of commerce and industry. From the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy we learn:

Strictly speaking, behaviorism is a doctrine – a way of doing psychological or behavioral science itself.

Wilfred Sellars (1912–89), the distinguished philosopher, noted that a person may qualify as a behaviorist, loosely or attitudinally speaking, if they insist on confirming “hypotheses about psychological events in terms of behavioral criteria” (1963, p. 22). A behaviorist, so understood, is someone who demands behavioral evidence for any psychological hypothesis. For such a person, there is no knowable difference between two states of mind (beliefs, desires, etc.) (4)

I would add a bit here. Forming beliefs in children, in order to shape their desires and, by extension, create more tools for social engineering, is at the heart of behaviorism--historically and currently. This is why school psychology has become a discipline that accompanies and, in many cases, overshadows teaching. That much appears to be self-evident. Thankfully, a love of reading and independent thinking can help to liberate students, to a certain extent, from the system designed to reinvent them as obedient and expendable laborers.

More than this, supplanting education with social indoctrination leads to problems beyond literacy, striking at the very fabric of communities, both large and small, urban and rural.

With this in mind, I read the landscape before me and proceed to the Anderson Campground and Gas Station in Eden, Idaho, a combination of services that actually works well. Anyway, although I've never been here before, I understand that smalltown charm has given way to discord for a number of years now, a trend that shows no evidence of ceasing. So, what will I discover as I explore?

Trouble in Rural America

As is my habit, I started a conversation with one of the front desk employees at the campground, eager to learn more about the area. Being roughly the same age, our views on historical America were similar, and she was able to enrich our conversation, addressing the deterioration of rural life and shedding light on recent years.

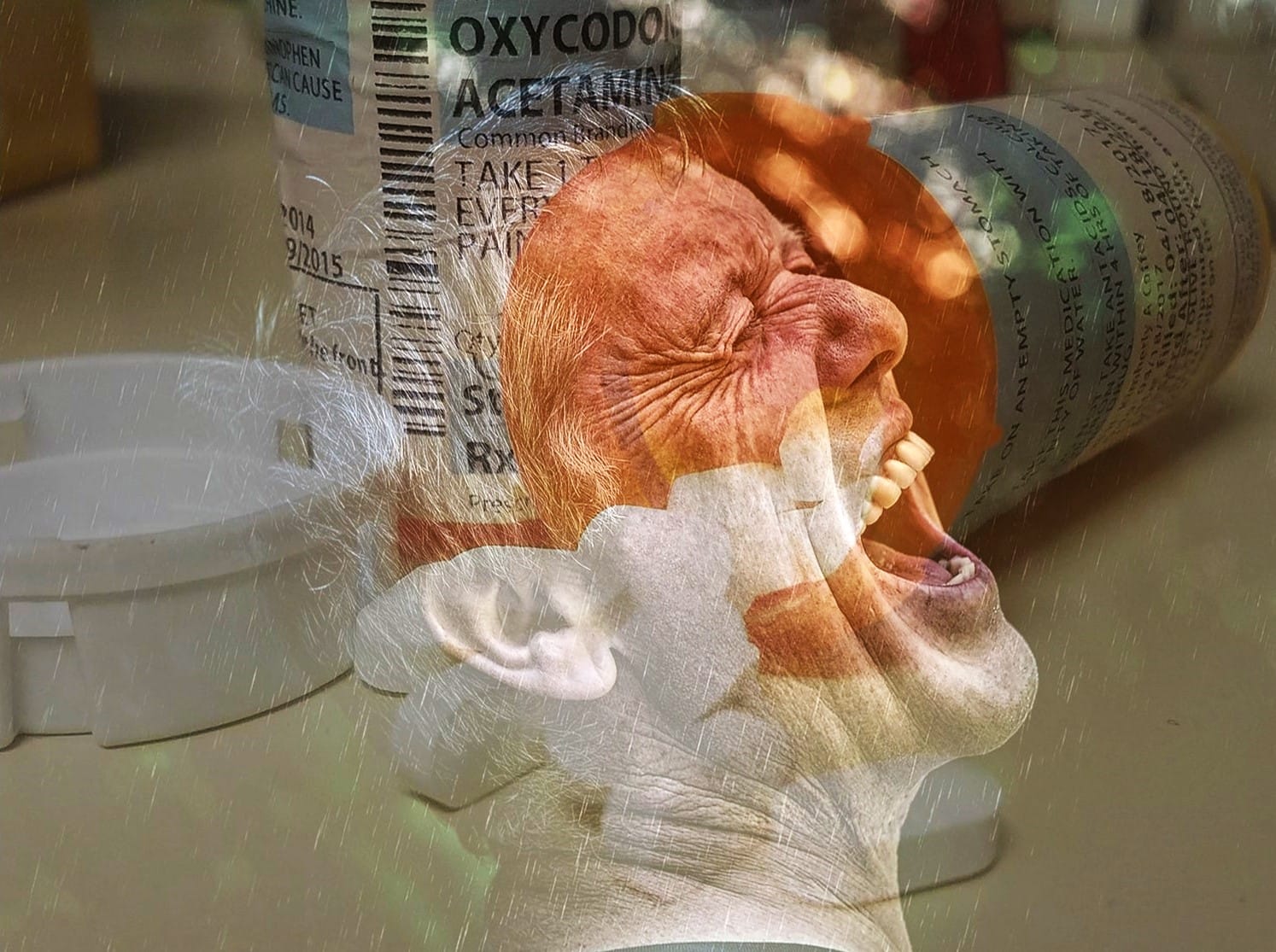

She recalled a time when the violence and drug problems of big city life were quite rare in the quaint towns of Idaho, which is certainly no longer the case. Indeed, we have seen opioid addiction consume once bucolic regions nationwide, as the economic woes unleashed during the 1980s continue to erode prosperity. And what about the impacts of high technology? Social media, that ubiquitous controller, impacts rural teens in similar fashion to their big city counterparts. Sadly, as the world becomes smaller through technology, social ills spread with terrifying speed.

At the end of our conversation, I was still eager to explore Twin Falls, but felt a bit more realistic about my rural journeys.

Regional Splendor and a Night at the Campground

If you stand on the deck of the Visitor Information Center, and gaze through the disorienting heights, the Snake River Valley comes into view as a majestic feature. With a number of other tourists, I watched boats drifting on dark waters, rested my elbows on rusted safety rails, and marveled at the rock formations carved by countless seasons of Idaho wind. I highly recommend exploring this area and meeting the wonderful people who call it home.

As for thoughts on education and the shaping of society, a recent incident comes to mind.

One evening at the campground, I watched as an older couple arrived with a teenage boy in tow. They unhitched their truck and settled in for the night, perhaps planning to leave at daybreak. Then, it happened. Dreadful loud music issued from the walls of their travel trailer, something popular with the young, and I found myself thinking back on Gatto, Flesch, and Blumenfeld. Yes, perhaps they were right. Or, if you favor behaviorism and the agendas of the rich, perhaps the containment and control mission of public schools has been a failure, not going far enough. Well, 2020 certainly took care of that, but I digress.

One can infer, from a preponderance of circumstantial evidence, that the social engineering of children--aka compulsory education--attends considerable problems. From epidemics of ADHD, and the rise of pharmaceutical dependence, to adult illiteracy and emotional health issues, there are many plausible correlations (and causations) to be identified. We will take that particular journey on another occasion. I can't wait.

Conclusion: High Literacy and Complex Thinking

Blumenfeld, most especially, reminds us that deeper levels of thought are generated when one reads, high literacy being a tool of the mind--a powerful asset available to rich and poor alike. Ideally, this process develops as children grow into adult readers, thinking and examining the world, engaging in discussion, and writing their thoughts for reflection. In Reading Theory Now, Eamonn Dunne, discusses the process of decision making--another powerful tool of the mind--and relates it to the act of reading:

Every decision is, therefore, divisive and elusive; every decision is a “split decision.” Like Caesar’s army crossing the Rubicon, it alerts us to a disjointed time, to a rupture in the moment that has always already been. It splits the time into a before and after. That d, lest we forget, is also for deconstruction, which is mad about the decision. There is no certainty in decision-making, just as there is no certainty in reading, in good reading at least. Decisions like true readings are haunted by the other, by the undecidable, by the alogical, by madness, by the perpetual displacement and the scission of the now that never simply is. (5)

As skillful readers of text (as well as life situations and our fellow humans) we can embrace the complexities that attend decision making, the divisive and elusive possibilities that confront us. With this in mind, I appreciate the way Dunne introduces the concept of time, "the now that never simply is." Reading allows us to traverse time, glancing back at the past, addressing the present, and theorizing about future possibilities. I think Dunne provides strong examples of Blumenfeld's "high literacy" concept. Now, all of this to what end?

In short, we can see why the controllers of society attack reading education, as doing so leads to a simultaneous attack on thinking and reasoning. Without the skills of high literacy, children are more likely to become obedient slaves of the system, unable to reason and argue effectively against oppression. After a few generations, the condition of enslavement simply becomes a normal experience of life--and the system remains unchallenged.

What Hegel taught that intrigued the powerful then and now was that history could be deliberately managed by skillfully provoking crises out of public view and then demanding national unity to meet those crises — a disciplined unity under cover of which leadership privileges approached the absolute. (6)

Can we apply Gatto's observations on Hegel to recent history, perhaps even dialectically?

As language skills dwindle, and communication is mediated (even dictated) by electronic devices, each succeeding generation will fall farther away from what was once called "the American Dream." And this is not a new phenomenon; as Gatto points out on pages 9 and 10 of Weapons, a gradual decline in literacy was noted as early as the Second World War.

I consider these things as I continue my stay in Idaho, enjoying comfort food and the beauty of verdant fields, the last remnants of our once agriculturally rich nation. As noted above, one can certainly chart the course of decline by studying the history of reading education. From there, we can also evaluate the development of other ills, including mass surveillance, drug addiction, economic deprivation, and the resurgence of fascism. However, lest we end on a dour note, we can always return to the realm of reading for refreshment and understanding, my favorite book being the King James Bible, "pre-recorded history" for those who are saved in Christ and cleave to his word.

A Note on the Critical Acceptance of John Taylor Gatto's Work

Although Weapons of Mass Instruction was a highly impactful book, initiating conversations worldwide on the subject of compulsory education, Gatto was certainly not without his critics. One of the main issues addressed, in various peer-reviewed articles, has to do with his use of un-scientific or anecdotal methods. Indeed, if one studies research papers on education--especially works devoted to behaviorism and school psychology--the data-rich content can seem daunting. And, as we know, the numbers can be slanted in various directions and contextualized in many ways. From there, our beloved policymakers can do as they wish, armed with peer-reviewed articles from sympathetic academics. For that reason, I agree with Gatto's clarity of presentation, his refreshing plainspoken analysis. However, like many confident academics, he tends to speak off-the-cuff rather than meticulously citing his references with endnotes. For the sake of verification, as well as the work of future researchers, citations in academic writing are quite helpful, even downright essential.

While I certainly do not endorse all things related to his career, I feel that Gatto's years in the classroom, as well as his obvious care for society and students, establish him as a very credible source. How many educational theorists and administrators spend decades working in under-funded public schools--laboring in the classrooms, not languishing in sequestered office spaces?

In short, the evidence speaks for itself.

As of this writing, in 2024, we can see the catastrophic results of American compulsory education--the literacy rates of graduating high school seniors being of particular concern. On the whole, the U.S. Department of Education recently reported that 21 percent of Americans read below a fifth-grade level and 19 percent are functionally illiterate. Beyond this, we must ask if reading comprehension and the ability to articulate analytical concepts were taken into consideration. If students can read, but lack sufficient understanding and writing skills, they are still compromised.

Moreover, we have also seen the slave mentality of the population metastasize alarmingly, few questioning the engineered crisis we experienced not long ago, most citizens believing everything that came from the media. Now, we must ask ourselves if such catastrophes were, on some level, facilitated by the educational system, specifically regarding how it shapes the behaviors, fears, and desires of countless children--generation after generation. Has society been programmed and propagandized through compulsory education, primed to believe the tyranny of satanic lies? I think the answer is abundantly clear. Kudos to Gatto, Blumenfeld, and Flesch.

As always, I thank you for your readership and wish you a wonderful day.

Works Cited:

(1) Gatto, John Taylor. Weapons of Mass Instruction: A School Teacher's Journey Through the Dark World of Compulsory Education (Gabriola, BC: New Society Publishers) 2010. (p.15)

(2) ibid.

(3) ibid.

(4) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/behaviorism/

(5) Dunne, Eamonn. Reading Theory Now: An ABC of Good Reading with J. Hillis Miller (New York: Bloomsbury Academic) 2013. (p.17)

(6) Gatto, pp. 12,13.

For Further Reading:

As a travel writer/essayist I approach subject matter from the vantagepoint of creative nonfiction. However, the avenues of thought that I reveal, and endeavor to explore, can benefit from deeper scholarly research. With that in mind, I have created a list of resources you can use to continue your investigation, a pathway into the subject of education and American literacy.

Katherine Bell McKenzie & Linda Skrla. Doing Critical Research in Education: From Theory to Practice (New York: Teachers College Press) 2023.

Blumenfeld, Samuel. Alpha-Phonics: A Primer for Beginning Readers (Old Greenwich, Connecticut: Deven-Adair Co.) 1983.

Ibid. Is Public Education Necessary? (Old Greenwich, Connecticut: Devin-Adair Company) 1981.

Ibid. NEA: Trojan Horse in American Education (Boise, Idaho: Paradigm Co.) 1990.

Flesch, Rudolph. Why Johnny Can't Read--and What You Can Do About It (Bronx, New York: Ishi Press International) 2015.

Gatto, John Taylor. The Underground History of American Education: A School Teacher's Intimate Investigation into the Prison of Modern Schooling. (New York: Oxford Village Press) 2006.

Narayan, John. John Dewey (Manchester: Manchester University Press) 2016.

Ruben, Beth C. Design Research in Social Studies Education: Critical Lessons from an Emerging Field (New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group) 2019.

Oord van, Jacob. Why Johnny Can't Read: The Real Reason (Or, Why We Need the Alphabet Phonetic) (Bristol, Indiana: Wyndam Hall Press) 2000.

"Phonetics" (Science, Jan. 3, 1890, Vol. 15, No. 361 (Jan. 3, 1890), pp. 5-7) Published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science.