An Abducted Image: Regarding Symbols of Disappearance

But whoso shall offend one of these little ones which believe in me, it were better for him that a millstone were hanged about his neck, and that he were drowned in the depth of the sea.

(Matthew 18:6, KJV)

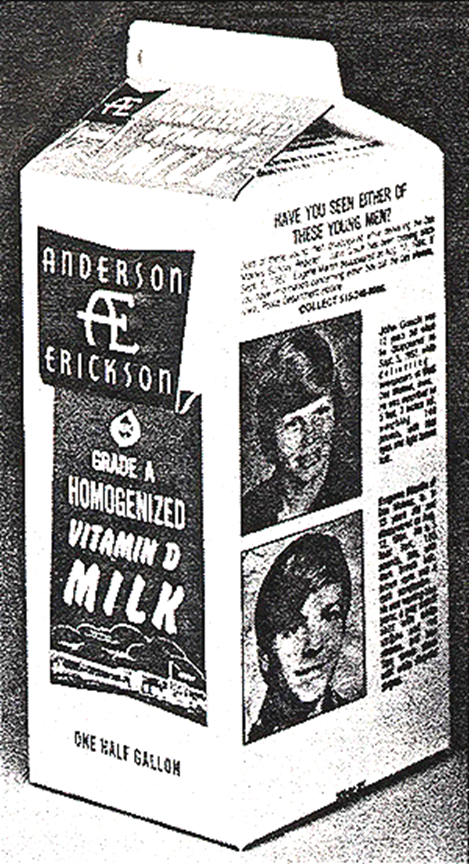

The phenomenon of loss, specifically as it pertains to probable abductions, has acquired its own visual language in recent years. Consequently, certain objects come quickly to mind when the subject is discussed, the white van and the milk carton photos of missing children being some of the most compelling symbols. And why have they become universal signifiers, impossible to ignore or minimize?

For starters, the sheer number of children that go missing in the United States each year is difficult to understand without a visual reference. Although the majority of cases regarding missing children remain unsolved, certain images have entered our cultural memory as a placeholder for resolution, and we will examine them here in some detail.

The Milk Carton and the White Van

In the face of high-profile child abductions, the dairy industry emerged during the 1980s to raise public awareness, at least for a time. After the disappearances of Johnny Gosch and Eugene Martin captured our attention, a unique solution was implemented to aid investigators. On the website of the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children, which receives funding from the Department of Justice, we read:

In September 1984, Anderson Erickson Dairy, local to Des Moines, Iowa, decided to use something they had right at their fingertips to push forward the mission. According to the Des Moines Register, the company decided to print two missing boys on the side of their milk cartons. For them, it was close to home, because the featured boys – Johnny Gosch and Eugene Martin – were local. Both boys had been abducted on their paper route: Martin less than a month earlier in August 1984, and Gosch in 1982.

However, in "Missing Kids: Milk Cartons Help the Hunt," we hear a different version of things.

Walter Woodbury, manager of a multi-state dairy, wanted to help in the search for missing children. The idea he developed has since attracted international attention. Vice president of Hawthorn Mellody Inc. of Whitewater, Wisconsin, Woodbury places pictures of missing children on Hawthorne Mellody milk and orange juice cartons. Almost 2.5 million half gallon and quart cartons are sold each month in Illinois, Indiana, Iowa and Wisconsin.

Authored by Vickie Quade, this article appeared in the American Bar Association Journal (Vol. 71, No. 3 (March 1985) p. 28) and provides us with different information. Quade goes on to say:

The cartons are being distributed as part of a collaborative effort with the Chicago Police Department. Since the first cartons appeared earlier this year, Woodbury has been contacted by dairies in California, Florida, Minnesota, Nebraska, New York, Washington, Canada and Australia that are interested in duplicating his efforts. He's also been interviewed on radio stations in Britain and Sweden.

Regarding the number of missing children in the United States, Quade writes that one million were reported in 1984, 15,000 of whom were from Chicago (p.28). Continuing, we find yet another discrepancy in the documentation of the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. On their website we read the following:

That original half-gallon milk carton seemed to inspire a movement. According to the Register, just a few weeks later, more dairy companies across Iowa began to participate. The program started to spread, hitting cities like Chicago and reaching as far as California. According to the National Child Safety Council, by December 1984, their nonprofit took interest and expanded the program by initiating the first nationally coordinated "Missing Children Milk Carton Program." Within weeks, the National Child Safety Council had partnered with more than 700 dairy manufacturers across the country, responsible for circulating cartons nearly everywhere.

The discrepancy before us, regarding the milk carton program and its inception, is symptomatic of a larger problem; we have no official agency that supervises and reports to the public about child abduction cases, no office that oversees the tracking of missing children on a national level and coordinates with state and local authorities. In short, no one answers to the American people and the families of victims. Although groups like The Missing Persons Center have appeared over the years, they are independent and deeply connected to corporations who provide security and investigative services, an interesting blend of nonprofit and for-profit endeavors.

Beyond the Missing Persons Center, we also have NamUs, the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System, which is designated as a "missing persons clearinghouse," a repository of "information and resources related to missing persons cases." Their website allows members of the public, law enforcement officials, and coroners to enter case information, all of which is vetted for authenticity. Beyond this, the NamUs system compares cases of missing and unidentified persons by date, geography, and "core demographic information." They also search for matches with advanced parameters related to scars, clothing descriptions, and tattoos. In addition to missing persons organizations, such as the ones mentioned above, there are also members of various communities who conduct independent investigations, as needed.

Although popular and widely utilized, we have limited information on the effectiveness of community programs such as independent social media campaigns, and, of no less importance, the billboard announcements provided by donors for certain cases. Metrics on the effectiveness of such campaigns would be helpful. At any rate, why do these combined efforts, and the vast databases compiled by multiple agencies, yield such modest results?

At this point, we need to pause and consider the magnitude of the phenomenon once again.

The number of children reported missing for 1984--in the pages of the ABA journal--is of no minor relevance. One million, for that year alone, is downright appalling and should have been headline news throughout the nation--although it was not. Today, the numbers are still just as troubling.

As of this writing, Child Watch of North America states on their website that roughly 800,000 children go missing each year--nearly 2,000 a day. Do we have nearly a million kidnappers operating independently, year by year, evading capture either by skill or luck? Or have millions upon millions of runaway children escaped the detection of law enforcement, leaving little to no evidence of their whereabouts? Groups like The Missing Persons Center, the Center for Missing & Exploited Children, and NamUs exist ostensibly to help answer such questions, creating databases for use by the public, as well as law enforcement agencies nationwide--sometimes even on an international level. However, something else needs to happen in order for this plethora of resources to yield results.

A central agency responsible for analyzing missing persons databases is essential. In the absence of skilled and thorough analysis, it's unlikely that meaningful connections between cases can be established. And with the sheer volume of missing children, it's very unlikely that no connections exist among the casefiles in question.

At this point, we must consider where our own analysis has led us, thus far. Let's return to the original theme of this essay, the abducted image, which speaks for a vast and complex subject. Regarding unsolved child abductions, we have two powerful symbols of this theme: the historic milk carton pictures of the 1980s, as well as the white van motif. So, why must we consider the latter?

Also known as the creeper van, this feature of urban legend certainly has a basis in reality. We include it in our present reflection because, over the years, it has become a powerful reminder of the dangers faced by children and teenagers. In particular, we have the case of Tara Calico, a teen who went missing in 1988 while riding her bike in New Mexico. Although she has never been found, a photo of a girl and boy was discovered, by chance, in a nearby parking lot, and is believed to have a connection to her case. In it, a teenage girl and younger boy are seen being held in the back of a van with an unfinished white interior, their mouths covered with tape and their hands bound.

As the 1980s witnessed a rise in abduction cases, and "milk carton kids" appeared in every household, the themes of "stranger danger" and "satanic panic" became imbedded within popular culture. A new and frightening phenomenon appeared to be rising. Indeed, we were routinely confronted by abduction cases on the nightly news, disappearances which, all too often, remained unsolved and faded into an emerging sense of paranoia. And that was the end of the matter for many unsolved cases--until the advent of social media inspired further investigation.

Recently, the true crime genre of YouTube has reintroduced old cases to the public, giving hope to families who still lack closure. With the intervention of time, witnesses sometimes feel obligated to come forward, and new technology aids investigators, so YouTube sleuths can be helpful. Although the quality of true crime channels varies widely, their creators continue to bring attention to otherwise forgotten cases. Now, we need to discuss a topic related to the subject of abduction which, although controversial and disturbing, bears consideration.

The McMartin Preschool Molestation Case: Satanic Ritual Abuse (SRA) in Context

The LORD trieth the righteous: but the wicked and him that loveth violence his soul hateth.

Upon the wicked he shall rain snares, fire and brimstone, and an horrible tempest: this shall be the portion of their cup.

(Psalm 11, 5-6, KJV)

Because SRA was introduced to the public by the media and depicted as paranoid conjecture--yet the crime has been proven to take place--we examine it here. So, how did the subject of satanism, and the ritual abuse of children, move from the realm of supposition to the halls of court buildings worldwide? Let's consider an emblematic case which took place in Huntington Beach, California.

The McMartin Preschool molestation case of 1984--which occasioned the longest and most expensive trial in the history of California--brought a certain term into common usage: "satanic panic." For those who are not familiar with the case, the preschool was located in an upscale Southern California enclave, and it gained attention after certain parents complained that their children had been molested by staff members. Sadly, what should have been a straightforward investigation soon became something of a television drama. Rather than focusing on specific pieces of physical evidence--involving medical examinations of the children and archaeological studies of the school building--most media outlets instead chose to label the allegations as satanic panic, mere inventions of paranoia. As of 2024, however, allegations from survivors of childhood ritualistic abuse have surfaced worldwide, putting things into perspective. Undoubtedly, the coming years will reveal a great deal, and historians will likely wish to scrutinize the acquittal of the McMartin defendants. Now, for our purposes, we will digress to examine a symbol related to such crimes, a window situated high above busy streets filled with onlookers.

A Distant Palace

As of this writing, you can search YouTube for an incident related to the United Kingdom. "Boy escapes Buckingham Palace" will yield a photo of what appears to be a naked youth repelling out of a high window, dangling above a courtyard as frightened bystanders observe. Above the search results, at the top of the screen, a disclaimer states that the photo chronicles an old television promotion and does not depict a 13 or 15-year-old-boy making an escape from the palace. So, there. Move along, there's nothing to see here, folks.

It's interesting to note that the once viral story is now more difficult to find on YouTube, ABP Sanija (a Punjabi language news agency) having one of the few remaining videos of the incident. And while alarming, the isolated image of a youth fleeing Buckingham Palace--naked and distraught--leads us to no definite conclusions, as it lacks formal context. We do not know who the boy was or what might have happened after he reached the ground. Members of the public are not privy to the details of the incident, the police investigations (if any took place) or the chats palace security agents undoubtedly had--which must have been rather interesting. At any rate, the footage has become an impactful symbol of exploitation and child trafficking, raising questions which still demand answers.

Evidence Seeking a Context

Were the unexplained disappearances of children (as well as numerous adults) rare, compelling symbols of abduction would have been less likely to emerge. The milk carton photos from previous decades, the white van of suburban lore, and the boy dangling from a palace window all demand our attention; they remind us that questions remain and must be answered. I repeat: Are we to believe that tens of thousands of kidnappers operate successfully, year after year, with little resistance from law enforcement, absconding with children who are never found? Thousands of abductors operating independently, all of them skilled and lucky enough to escape, should be newsworthy. And yet, major news outlets rarely address the subject of disappearances in a meaningful way. Why? Although the answer to this question must remain deferred, for the time being, we still have much to ponder.

In addition to the numerous allegations of child abuse now being discussed--most of them ignored by the media and the various police agencies in question--we must also regard those who speak out in support of victims. With that in mind, let's consider what happens when a member of the academic establishment breaks tradition in order to investigate a controversial subject, exposing the power structure rather than supporting it and basking in the luxuries of tenure. We continue our journey with a 1981 cable access program, the Alternative Views News Magazine, and learn about the professor who risked everything to speak the truth.

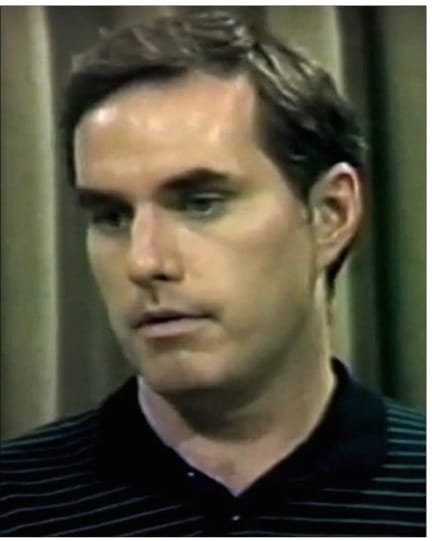

Professor Tom Philpott: Symbol of a Crusader

The program begins with the images and music so characteristic of the era, as the narrator introduces their topic of discussion. For roughly the next hour, Philpott and a panel of journalists discuss Boys for Sale, a documentary on child trafficking. When the professor appears, he speaks in earnest tones, as the moderator looks on with a rapt expression, and the audience of 1981 learns about something few will wish to believe. So, who was this historian and activist?

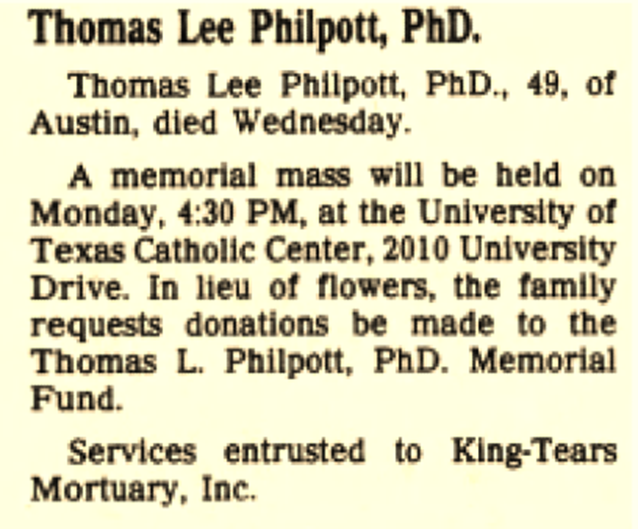

A listing for a Thomas Lee Philpott of Austin, Texas can be accessed online at find a grave, noting that he was born on January 21, 1942, in Cook County, Illinois and died on October 9, 1991, in Austin. He was 49 at the time of his passing. Although Philpott was an associate professor of history at the University of Texas at Austin, and conducted considerable research on labor and housing in Chicago, he is mainly remembered for something a bit less ordinary. His research into the world of child trafficking, specifically related to Houston, Texas, stands as a heroic investigation.

Even now, very few (if any) professors risk publishing work that exposes pederasts and pedophiles at high levels of power. In point of fact, tenure in the social sciences is rare these days, and criticizing the establishment might lead to a loss of employment, which was less of an issue in Philpott's day. At any rate, we learn about his endeavors, as well as his complex personality, in a May 1982 article from Victoria Loe. "The Case of the Campus Crusader" first appeared in Texas Monthly in the True Crime department and is archived on their website. However, another version, with the original graphics and layout beautifully preserved, can be found on the Internet Archives website. From Loe we learn:

Every university has its Tom Philpott; there's always at least one professor who turns up at the center of every controversy, who seems to make his living as the administration's quasi-official gadfly and whipping boy (. . .) Tom Philpott's fondest dream is to be remembered among the great American social crusaders, to join a pantheon that includes Jane Addams, Clarence Darrow. Jacob Riis, Frederick Douglass, Robert Kennedy, and Martin Luther King. (p. 164, Texas Monthly, May, 1982)

In those days, professors were actually paid a living wage and able to enjoy academic freedom, even when they challenged the power structure. And Philpott excelled in this area, as he aspired to the heights of activism. Then, in 1979, he came across the work of John Kells and David Glodt, the former being a prodigious 19-year-old journalist, and discovered a compelling research topic. Boys for Sale, their documentary on child sex trafficking in Houston, would inspire Philpott to investigate a dark and horrific aspect of our society.

During the Alternative Views discussion, Philpott revealed much about the situation in Houston, identifying the culprits as "the pillars of our society." He continued by stating that those involved are connected to the financial, industrial, and educational institutions of our society, the "elites," including congressmen and senators (Boys for Sale, Part 1, 28:10-28:59).

Throughout the program, Philpott speaks emphatically, at one point revealing a collection of newspaper clippings and research materials in his possession. Moreover, he disclosed plans to write and teach extensively on the subject of "child prostitution" in the United States, naming the guilty regardless of their elite status. Then he was shot. In her article, Loe recounts the details of a truly bizarre episode in American academic life.

One day, Philpott heard the sound of intruders who had broken into his apartment, two men who, according to his testimony, shot him before making their escape--events that transpired shortly after his appearance on Alternative Views. And that's where clarity gives way to a variety of conflicting reports, the police stating that they found more bullet casings than Philpott's testimony accounted for, some people believing that he had actually shot himself. The fact that Philpott had previously attempted suicide, according to Loe's article, did not help his case, and the situation remains in doubt to this day. What is unchallenged, however, is the fact that violence often comes to those who interfere with child trafficking operations.

As for Loe, she paints an interesting portrait of the crime-fighting history professor, calling his impassioned lectures, "the greatest show on campus," and, more importantly, providing details about his mental health journey. Exactly how his mental illness became known to the University of Texas community, to the extent that a journalist could reference his condition in glib fashion, remains unclear. Moreover, we also find that Philpott's antics as a "gadfly" are emphasized by Loe, and she allows them to overshadow his academic work. Published the year of his death, The Slum and the Ghetto: Immigrants, Blacks, and Reformers in Chicago, 1880-1930 represents a large part of his research. Regardless of his emotional state, Philpott was a serious scholar.

Loe goes on to chronicle his downfall.

Meanwhile, Philpott was falling apart. He collapsed several times- in a photocopy shop, at a McDonald's, at the theater. Finally he checked into a private hospital, where doctors diagnosed him as manic-depressive and prescribed tranquilizers and lithium. But even as his medical condition improved, his marriage broke up for good. (p. 9)

In short, Loe's article is worth reading, but it calls into question the journalistic portrayal of Philpott, her tone often conveying sensationalism rather than objectivity. Perhaps her treatment of the subject reflects the nature of his investigation. In other words, powerful individuals identified by the professor for their rape of children would, very likely, have favored discrediting him, so a sensationalized article would have met with the power structure's approval. It's also worth noting that Philpott's projects, the articles and books he planned to write about child trafficking, are nowhere in evidence today. As for his death, that also remains a subject of controversy.

Several years ago, I was able to find a memorial for Philpott on the University of Texas at Austin's website. Interestingly, I am now unable to locate that page. I did, however, find an entry on the "Life, Death, and Iguanas" blog by Marc Newhouse where the memorial is recorded:

Thomas Lee Philpott–associate professor of history, fiery Catholic moralist and polemical leftist, and charismatic and much-honored teacher–ended his life on October 9, 1991, in Austin, Texas, after a yearlong illness. He was 49.

In some references, the "illness" in question is linked to bipolar disorder.

And there the matter rests, at least insofar as the official version goes. Having become famous online, the tale of Philpott's crime fighting, his research, and the emotional struggles of his life, will likely persist as symbols of child trafficking in the United States; those who deny the prevalence of such crimes, and their impact on our culture, need only reference his work and the questionable details of his passing. We can regard Professor Thomas Lee Philpott's work as a symbol of protest, resisting an evil too vile to ignore.

In Conclusion

Because this essay is mainly a reflection, and not a research piece, I will leave it to you, my readers, to search online for SRA survivor testimonies. You can decide whether or not you find such allegations credible and worthy of additional investigation. I will state my position clearly: I believe that many survivor testimonies are credible and deserve to be investigated, although they rarely are, suggesting that the crimes extend to a very high level of power. My goal, at this time, is to make you consider a subject which is often misrepresented by the media or simply ignored. And, yes, we must ask how far such crimes extend. In other words, how much of the power structure is involved with satanic ritual abuse, keeping their sins, and those of their fellows, concealed in the darkness of lies? It would be helpful to read Philpott's research notes and the drafts of his work. However, in the absence of his writings, we have the strength of imagery, symbols of abduction deposited within our collective memory; the milk carton photos, the white van of urban legend, the boy dangling from Buckingham Palace, and, not least, the life of a crime-fighting history professor speak volumes, testifying for the children who have gone missing.

And have no fellowship with the unfruitful works of darkness, but rather reprove them.

(Ephesians 5:11, KJV)

For Further Reading & Research:

Although not discussed above, the Doe Network is an organization devoted to tracking missing people internationally, sometimes coordinating with NamUs. Here, I include information from their website which states the scope and mission of their work:

The Doe Network is a Non-profit 100% volunteer organization devoted to assisting investigating agencies in bringing closure to national and international cold cases concerning Missing & Unidentified Persons. It is our mission to give the nameless back their names and return the missing to their families.

We hope to accomplish this mission in three ways:

By providing exposure to these cases on our web site.

By providing credible potential matches between missing and unidentified persons to investigating agencies.

By striving to get much needed and deserved media exposure to these cases.

They go on to explain their numbering system in detail. So far as I can tell, it is specific to their organization and does not correspond to the tracking systems of NamUs, the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children, or the Missing Persons Center. As an example of their numbering system, the Doe Network offers the following: Casefile 91UFTX

- 91st individual added to their database for the given category.

- UF (Unidentified Female)

- Located in Texas

Here, it's important to note that the casefile number does not reflect the current number of unidentified females with active cases in their system, as their tracking does not include updates for closed cases. The Doe Network states this clearly on their website.

In the area of SRA, there is a great deal of research to consult. The problem, however, has to do with the scope of the phenomenon and the methods by which credible allegations are documented and pursued in the courts. Also of note is the sheer number of blogs, articles, books, and videos in circulation regarding the subject, offering information on numerous victims and survivors of satanic ritual child abuse. With this in mind, there are certain individuals who have come forward with testimonies that bear consideration. If you choose to conduct your own research, you may wish to investigate the cases related to the following individuals:

- Mary Knight

- Anneke Lucas

- Fiona Barnett

- A 1989 60 Minutes (Australia) interview with then 15-year-old-Teresa, conducted by journalist Ian Leslie. The piece chronicles the abuse suffered by the British teenager at the hands of her family, members of a satanic cult run by the girl's grandmother. It was uploaded to the 60 Minutes Australia YouTube channel on August 4, 2020.

- Kibbi Linga

- "The Survivors of Satanic Ritual Abuse" Part 1. This video was uploaded to the Dare to Fly YouTube channel on May 27, 2020. It contains numerous survivor testimonies and offers commentary from the channel's creator.

Books of Interest:

Congram, Derek. Missing persons: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on the Disappeared (Toronto: Canadian Scholars' Press) 2016.

Kennedy, William H. Lucifer's Lodge: Satanic Ritual Abuse in the Catholic Church. (Hillsdale, NY: Sophia Perennis) 2004.

Ross, Colin A. Satanic Ritual Abuse: Principles of Treatment (Toronto: University of Toronto Press) 1995.

This piece is intended for public education. All images and web materials are reproduced under the Fair Use Clause of U. S. Copyright law.